Rig-For-Rescue

Suspension Trauma

There has been some new research looking at the onset of suspension trauma. This was presented at the International Commission for Alpine Rescue (ICAR) 2018 congress in Andorra. This was a study using human trials and the key findings were:

- Pooling of venous blood in lower legs stabilises after 5 minutes.

- 30% of motionless participants collapsed within 15-45 minutes.

- Collapse occurred without warning or change in clinical signs.

- Time from collapse to cardiac arrest maybe only a few minutes.

- Rescue of a motionless person on a rope is urgent.

This video (from Topograph Media) presents an excellent summary of the study:

Rig-For-Rescue

People have used rope access techniques to undertake work at height for decades. These techniques are now quite specific and well defined by various industry groups and their Codes of Practice (COP). Each organisation has subtle differences in approach but they all strive to provide a framework for safe places of work.

One of the fundamental tenets with modern rope access techniques is that operators always have at least two separate points of attachment to a solid structure. This is generally provided though two ropes: a main rope and a backup rope. The main rope will be used for ascending and descending. If the main rope is compromised then the backup rope should catch the operator with a system capable of limiting the arresting force to an acceptable value.

The new study of Suspension Trauma above reinforces the need for rope access technicians to have a sound and efficient rescue plan in place for each job that they do. If a motionless person is suspended be rope, it is imperative that they are completely removed from the system as soon as possible.

Technicians are required to undertake a thorough analysis of hazards and document a formal Risk Assessment prior to starting work. This will normally include a rescue plan detailing any additional equipment and rigging that will be set up in advance to facilitate a rescue. This has become known as ‘rigging-for-rescue’.

Traditionally, such rescues have involved approaching the victim and performing a direct contact rescue. Most organisations are now encouraging operators to anticipate the need for rescue and, where possible, establish systems that facilitate remote recovery from a safe stance. In reality, each work site is different, and technicians should understand the rescue options that may be applicable and be able to make appropriate decisions.

Rescue Options

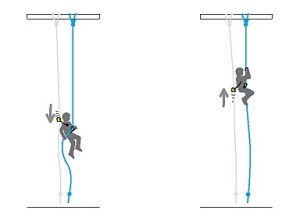

Send a second operator down to facilitate a rescue

This is the traditional method trained for and used by rope access technicians and adventure operators. Advantages of this system include:

- basic first aid can be delivered quickly if required.

- the rescuer can gather first hand information about what problem has occurred and make decisions accordingly.

Disadvantages of this system include:

- the rescuer is potentially exposed to the same environmental hazards as the victim.

- the rescuer is exposed to the risks of operating on rope at height.

- the load on the system is potentially increased to a 2 person load.

- once over the edge, the rescuer is committed to a single course of action.

Lower the victim to the ground

Many outdoor recreation operators have been rigging this option into their system for many years. On a top belayed abseil/rappel system, the main line is rigged to be releasable. A separate top-belay line can be used to secure the system while the main line is released. Both lines can be used to lower someone to the ground if necessary.

The international standard, ISO22846-2:2012, which applies to rope access work, includes the capacity to lower an operator to the ground as one of the requirements of a Simple Rope Access Worksite. Lowering a stuck operator to the ground can be achieved with a simple addition to the standard twin rope access method. The knotted attachments at the top of the main and backup ropes are replaced with releasable devices. Operators need to ensure that there is enough rope in the system to be able to lower the operator all the way to the ground, that they can see the entire descent and that there is a safe place at the bottom to access the victim.

Advantages of this system include:

- it can be fast.

- the rescuer is not exposed to environmental hazards or the risks of operating on rope at height.

Disadvantages of this system include:

- some sites will not have reasonable access to the ground.

- the operator at the top needs to have good visibility of the entire height of the drop.

- some sites will require significant amounts of extra rope to reach the ground – which the operators may not have.

The following video presents a range of lowering options:

Two questions that should arise from this video are:

- Could the Italian hitch behind the ASAP increase the stopping distance?

- What if the ASAP catches on the rope?

These questions are both discussed in this video:

Raise the operator to the top

In many cases, lowering is not an option, and technicians should know some systems by which raising can be achieved. Generally those working over water, on complex sites without ground access, and in confined spaces know that lowering an operator further is often not an option, and that sending a second person down may be exposing them to significant environmental hazards such as noxious gases.

Advantages to this system include:

- a second operator is not exposed to risk at height or any environmental hazards.

- a haul can be achieved using minimal equipment.

- it does not require access to the bottom nor a clear descent route.

Disadvantages to this system include:

- requires a higher level of competency from the rescuer.

- may take more time than a simple lower to the ground.

- may have to negotiate an edge or other obstruction at the top.

There are several raising options that are good for operators to know and understand. I will outline three below.

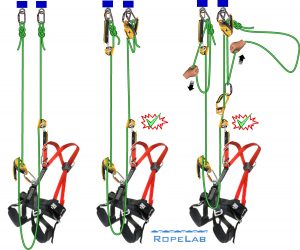

Traditional Raise

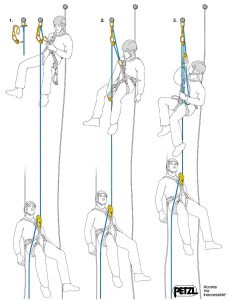

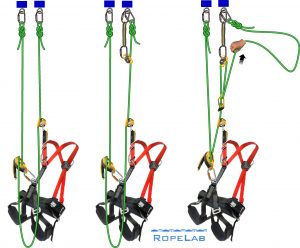

A common method uses the old-school “assume you only have what’s on your standard rope-access harness” and looks something like what is shown below. The images from left to right show the steps to set up the hauling system. The hauling is completed on the right hand rope while the backup rope is taken in on the left. The photographs show the same system applied using real devices.

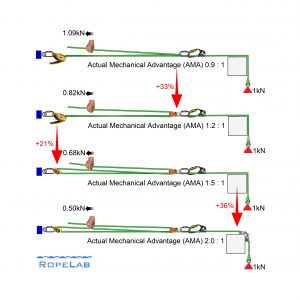

I set this system up in the lab and measured the actual hauling tension applied to raise a 100kg technician for each of four different scenarios. The first scenario is the same as the traditional method shown above. In progressing from one scenario to the next, I made one change to increase efficiency and re-measured the applied hauling tension.

The results are interesting. In summary, they show that:

- The Ideal Mechanical Advantage (IMA) of all these systems is 3:1. The IMA does not account for friction and other losses in the system.

- The first method with the rope over an edge had a measured Actual Mechanical Advantage (AMA) of 0.9:1. This is worse than a straight pull of 1:1!

- Adding a pulley at the rope grab improves the AMA to 1.2:1.

- Replacing the I’D with a ProTraxion further improves the AMA to 1.5:1.

- Finally, adding a low friction edge-roller brings the AMA to 2:1.

- Adding each of these elements alone does not make a significant difference however, combined, they double the AMA and result in a system that can easily be operated by a single person.

- Note: a single person with good footing can apply 0.5kN of tension but certainly not 1kN (for continuous hauling).

Breaking into Tight Lines

There are other options for raising an operator. One that is worth knowing and practicing is known as “breaking into tight lines”. This skill allows raising in situations where the ropes tight and have been knotted directly into an anchor.

Petzl describes the following “Spanish Balancier” method on their website here.

There are a few variations on this and, from a teaching perspective, one that seems slightly better adds the use of a foot loop and is shown in the next two graphics.

The key difference with this method is that the foot loop initially effects a 2:1 break-in but this quickly becomes a 3:1 once there is enough slack in the system to introduce the second rope grab. I have tested this system while suspended on the anchors and had no problem performing the break-in and straight lift of a 150kg suspended steel mass. From a teaching perspective, participants seem to grasp counter balances far more readily if they stand in a foot loop. This system is also easy to operate with horizontal systems by pulling on the foot loop (rather than standing in it).

Confined space / Crevasse rescue rig

There are many options for raising rigs however we should acknowledge a technique used by alpinists for many years. Rescuing a fellow climber from a crevasse is problematic because the rope normally cuts into the snowpack. To make this easier, alpinists generally use a technique that involves dropping a loop and effecting a 2:1 raise of their partner. One huge advantage of this is that half the weight of the suspended climber is supported by a non-moving rope – thus friction is only an issue for half of the system.

It is conceivable that we can use a similar approach, especially if the technician is working on a closed loop of rope.

This system relies on there being no tangles or obstructions in the ‘dropped loop’, especially around the suspended technician however, if all is clear, then rope will just bump through the descender and provide a significant reduction in the effort required to raise. Another extremely unlikely event that must be acknowledged is the possibility of a rope cut just on the anchor side of the descender. If this did happen then ASAP may not grab the tail and the technician would fall.

Summary

While it is great that the term “Rig-For-Rescue” is thrown around readily in the rope access community, I am not convinced that technicians have really thought what this should mean. “Rig-For-Lower” is relatively simple but there are not many sites where this is going to help. If “Rig-for-raise” comes up then it seems all too easy to fall back on traditional methods built around descenders and carabiners but I don’t think this is good enough.

I think we should be revisiting options for raising including breaking into tight lines and the addition of a few simple pieces of kit to the standard technician harness.

This simple combination of Petzl Rollclip, Tibloc, and MicroTraxion is cheaper than a standard descender and gives technicians so many efficient possibilities. This efficiency should mean that raises should always be possible with simple 3:1 systems which, in turn, get the incapacitated technician up faster.

© Richard Delaney, RopeLab 2018

Add a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

We train for this very thing for use during recreational bouncing of pits. Worst case scenario is a single rope rigged and the last man down has an issue. Now everyone except the patient is as at the bottom with no way to get back to the top, only one rope, and the patient is now hanging on it halfway down. So, our training consist of a bottom-up rescue where we climb the same rope the patient is on. We carry the end of the rope with us as we climb. Once we reach the patient then we climb past them (same as doing a knot pass). Once above the patient we set an anchor on the mainline (prussic or rope grab), attach a descender, then rig the tail of the rope we hauled up through the descender and back to the patient’s harness. Lock off the rope, then use a mini set of 4s or counterbalance to unweight the patient from their descender (if needed). Once free from their descender it’s simply a matter of lowering the patient to the ground. Th other option is to continue to climb the rope and go over the top, then setup a haul to bring the patient up.

Hi Richard,

I wonder about the quality of the evidence presented re: suspension trauma. I totally agree with the recommendation, however I don’t see the relevance of the motionless person hanging on a rope (this person is already sick if they are able to hang motionless for 15 min plus) and I doubt there is any evidence for the statement re: time to cardiac arrest (ethics approvals for turning dirtbag climbers into cadavers are harder and harder to get). Are there any links to the study? Obviously this doesn’t change the need to rig for rescue but being a topic I’m often asked about this is interesting to me. My take is – access the person, move them to an area you can manage them (like the ground or a ledge) follow your basic principles of first aid. Airway, Breathing, Circulation blah blah.

Hi Cam, I too have been waiting for the links to the study – I’m hoping they’ll come out on the ICAR website before then next meeting in October 2018.